If you want these as emails, scroll to the bottom.

9/23/2025

Family Business: Praying and the Small Stuff

Family Business: Praying and the Small Stuff

It’s been a while (month) since I’ve updated things here, and the world has dipped even deeper into madness. For the most part, we can chalk this up to life being genuinely busy in ways it often isn’t. My day job has reached a fever pitch, lovers from out of town stopped by for a visit, and things at my church have begun to gratefully take up more of my time.

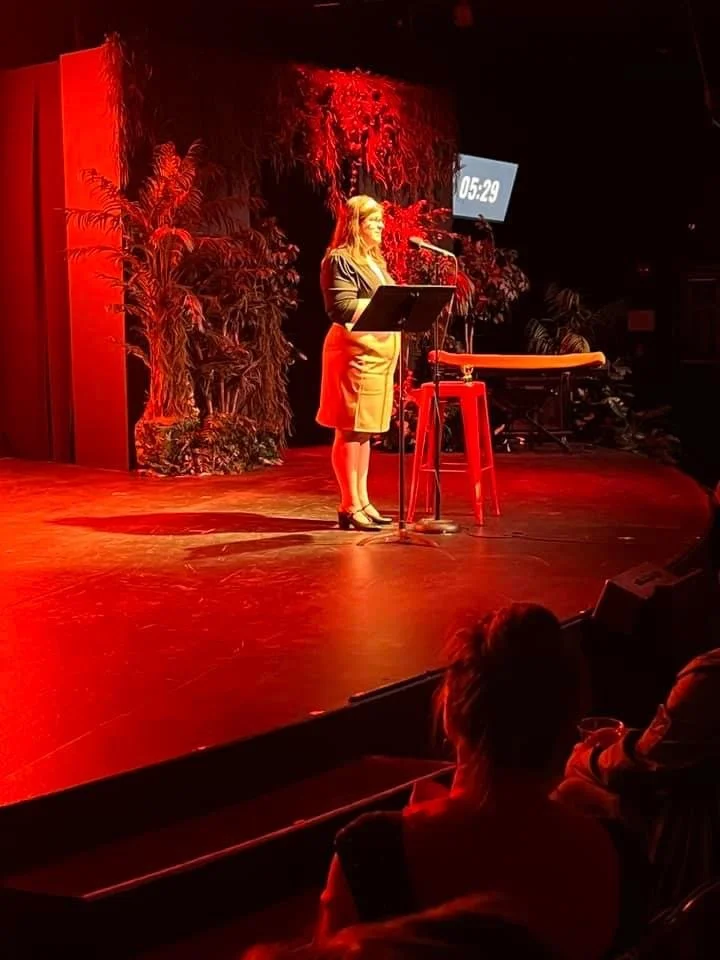

But I’ve missed writing, and when I was offered a slot in a variety show with the theme “Small Wins” I decided to write about prayer, E.T., and the little things. Prayer has become more and more the center of my creative life. It’s hard lately to write with anything else in my heart but calls to God. Sometimes I worry that makes me hard to relate to. A "queer trans Christian” feels like an oxymoron, culturally speaking, especially as so many “Christians” seek to dismantle queerness as a cultural identity through politics and violence in equally cruel measures. But here I am, a handmaiden of the Lord, writing all I know how to do.

The double edged sword of growing up Catholic is that I always have a set of prayers memorized, but have recited them to the point where praying doesn’t feel like praying.

Unless I really focus, it doesn’t feel like anything. Maybe school. It feels like school. This is most true of the “Our Father.” I’ve said the prayer a thousand times, and have always struggled with it. Thinking of God as my Dad makes it very hard to talk to Him.

I think we can chalk this up to the organ music, the robes, the smoke, and hauntingly realistic crucifix at the church I grew up going to. I used to be scared to pray there, or, more specifically I used to be self-conscious about praying about the small stuff in such a big place.

And when you’re a kid, it’s mostly small stuff. The Our Father again had to take a lot of accountability here. Forgive us our trespasses? I’d been at home in the basement playing Scarface the Videogame all weekend. What are we talking about?

Going to see my Father at his work to talk about a test that didn't go my way or how they took out Batman Beyond out of the Toonami block did not feel appropriate. I already felt terrible as a child telling my dad-dad about literally anything, let alone my God-dad.

Despite being all-powerful and all-knowing, I still felt like God had more important things to do, like make more mountains or asteroids or contracts for complex commercial timber deals in the Pacific Northwest, y'know, dads.

It followed into adulthood, where a fearful respect for my father shifted into an frosty silence, and a fearful reticence around God became a vehement disbelief. It was easier to get angry than risk getting disappointed again. I stopped going to church.

I stopped praying. I stopped trying to connect with my dad about anything but the last Clint Eastwood movie I watched. I stopped talking to God about anything but the words He taught me to say. Small stuff would shrivel on the vine, big stuff would timber until the forest was flattened. It stayed flattened for years.

Shortly after I transitioned, I started going back to church for reasons too complicated and esoteric to get into. I loved church, the community, the music, the structure, but some kinds of prayer were still difficult.

What do I say to my Father? How do I trust my Dad to love me after our estrangement? How do I pray about the small stuff?

Then, right when I needed it, the Our Father again. In Church one Sunday the pastor explained that Jesus taught us Our Father, not just because the Father was important, but the Our. Like every other thing lately, it’s about those fussy little pronouns. Our Father isn’t about where we are in relation to God, it’s about where Jesus is in relation to us. He taught us to pray so that we could talk to each other like family.

If God is Our Father, then Jesus is my Brother. And I love my brother. And I can tell my Brother whatever!

It’s a lot easier now. Folding my hands and spilling my guts. The good that I’m thankful for. The bad that threatens to break me. My brother gets it. He’s been there. I just close my eyes and share.

Brother, I yelled at an email today.

Brother, you won’t believe what happened at work.

Brother, I ate mac and cheese for the last three meals. I think I’m losing it.

Brother, I don’t know how to stay happy when the government thinks my happiness is a terrorist act.

Brother, I have to make cookies for a birthday party and if they’re not good everyone will hate me.

Brother, I feel like everyone needs help and I have only so much to give. I feel thin. When that woman touched your cloak and was healed, you almost fell over from the exhaustion of. Brother, I am exhausted and half so capable of miracles as you. What should I do?

But also, Brother, thank you for airplanes, for good books, for poetry, for voice memos. For impact play. For clean bathrooms. For performance venues with good parking.

For bbq sauce and cucumber salad recipes on Instagram. For phone calls where all we do is fall asleep. For spaces like this that let me talk to people the way I talk to you.

For churches that don’t make me feel like my Dad is gonna walk in and yell at me again.

For E.T. at the Plaza. For seeing E.T. with a friend who didn’t know he was Henry Thomas, while I didn’t know I was Drew Barrymore, and neither one of us knew we were E.T. the whole time.

Thank you for stories where sensitive boys help misfits in wigs get home safely.

Thank you for helping me phone home when I need you.

Thank you for people in my life that it feels like praying to talk to. Thank you for family whenever I need it.

Thank you for good men who are like brothers and fathers all over again.

Thank you for being my brother. I love you. Talk soon.

Amen.

Yours with an open mouth

-B

8/15/2025

Keep the Feast: Pica Disorder and the Desert’s Call to God

Keep the Feast: Pica Disorder and the Desert’s Call to God

Recently I was invited to participate in my favorite live lit event: Write Club, where writers are given opposing topics and pitted against one another. My friend Dani was given “moist” against my “dry.” As we set about our process, we kept in touch exchanging trash talk and encouragement in friendly intervals. When it came time to perform against one another I was suddenly terrified of how vulnerable this piece feels. A minute from show time I ducked into a quiet, dark alley and prayed, offering my performance to God. His will be done. There’s a lot of solace in prayer. It’s something I want to pursue in my writing going forward. For now, enjoy this piece about mysticism, pica, and the deserts we stuff inside ourselves.

LISTEN to the audio of my performance here:

Last week I tripped and spilled a can of baked beans on my kitchen floor. I had to use a real towel to clean it, because I was out of paper ones. Again. And I was out of paper towels -again- for a reason shameful enough that I tried to write three drafts of this thing before finally settling for this one, where I just tell you the truth:

I was out of paper towels because I ate them all.

I have pica disorder. It means I sometimes eat things that aren’t food. This mostly means chewing on paper towels until they become these dried out little tumors I like to call “paper bones.” The last time I cleaned my apartment, I had enough paper bones to fill my vacuum. It’s a stress thing. When I am overwhelmed or overworked I will whittle a roll down to nothing one dry sheet at a time.

I promised myself I would never write about this. I could write about sex or BDSM or anything I wanted but never this. Too gross. Too weird. But now I need to. I need to talk about what the stress of the world is doing to me. I need to talk about how I’ve eaten enough paper towels in the last 7 months to put all the paper I ever ate before to shame.

And this is all about shame.

It started when I was younger, around eleven, and sent home with my first bad grade. I ate it, right there in the school hallway. I destroyed the evidence before I could show my parents, but when you swallow a secret, it stays with you. Like gum. Like disease. It stays in your body and spreads like sunlight over death valley until every garden in your heart is cracked and brown and burning.

The report card was just another brushfire. I was already a conflagration of secrets by then. Ever since the older boy when I was nine touched me when I didn’t want him to and I didn’t tell anyone.

Nothing grew in my body after that but sand dunes and shame. I was a desert son with a sun in my stomach. I furnaced whatever I could into flames, hoping the smoke signals would send help. If only someone could read them.

Nothing takes me back to that shame quite like my pica. It makes me feel like a freak. There she is, irony’s bastard daughter, the poet who eats paper, who writes haikus to season the scraps. Go ahead, ask her how to publish a book, and ask her the difference between the taste of Quilted Northern and the Quicker Picker Upper (little more mint on Bounty for some reason).

I am a freak, at my freakiest, right now. I go to work and chew paper towels. I watch the news and chew paper towels. I hear about how my friends are getting priced out or evicted one after the other, and I chew paper towels while I do what I can to help. I am terrified and dry as a desert inside.

My one comfort, though, is this is not without precedent. I’m a Christian. Hell, most of my role models are freaks just doing their best. Teresa of Avila would levitate while she prayed and had wet dreams about angels. Mary Magdalene de’ Pazzi would wear a corset of nails and lick the wounds of lepers while she gave them comfort. Catherine of Siena wore an invisible wedding ring made of Jesus’ foreskin. Freaky women are the stained glass windows of my church in the wild. Every step I take is lit by their colors.

So I chew paper like locusts in dark honey. So I grow out my hair and ready my hands for good work. So I whip myself after reading the Psalms. So I softly say blessings over the bodies of sleeping lovers.

When I go into the desert now it isn’t to hide. It’s to pray.

I’ve been praying a lot lately. For guidance, for courage. I pray to my freaks for the strength to keep going. Flannery O’ Conner once wrote in her prayer journal “don’t ever let me think, dear God, that I was anything but the instrument for Your Story.” I have been swallowing my version of His story for too long. There has to be a reason bible pages are the worst tasting paper I’ve ever tried. I was made to spit them out, baptized with my own tongue.

And it would be easy to just swallow my faith these days, when the leaders of churches want to kill people like me, when the Pope says my gender is harmful to families. When Jesus says love thy neighbor and they call empathy a sin. They want to tell me I’m alone.

I am alone. Alone with God in my desert, swallowing paper to clean up the spill inside. Things are getting hot. The air is too dry to breathe for most people.

But I am not most people. I am a woman of the desert, sand-blasted and fire-glazed to handle it. I’ve been preparing all my life for these temperatures. Like Teresa. Like Mary Magdalene de Pazzi. Like Joan of Arc. I am a freak on fire with the truth God gave me. Because God said “speak” and I listened to Him and not the institutions wearing his face.

The desert is hot, but not as hot as I am tonight. Right now. Lit up like a tungsten bride of Christ. My burning insides are hot enough to give off this light for miles.

Before tonight I had enough paper bones to skeleton my closet. Before tonight I wasn’t going to talk about eating paper. Ever. But tonight, everything’s out in the open, all my secrets spilled on this stage.

Now you know what I am. What we all can be when we burn the shames inside us.

I am a miracle. I am a girl who swallowed a desert and spit out the voice of God. A girl who wears dresses the color of smoke while she tries to keep the people she loves warm. I am a girl who loves Jesus and her own trans body, enough to stand up to Christians who hate it.

I am a girl who eats paper and breathes fire.

7/5/2025

Reading Books at the End of the World

Reading Books at the End of the World

I originally wrote this for a hope-punk variety show called Joy Deficit. Every month’s show is themed. This show’s theme was “Books.” When I initially applied, I asked if I could read an older piece about finding my voice by reading aloud. Soon after, though, I realized I wasn’t done talking about the healing power of reading to someone you love. So I wrote a draft of this piece. I then tweaked some of the language and here we are. Things are bad. They feel impossible. But reading to my partners, to my friends, is a way I stay afloat. I want to do my best to honor that. This piece is my best attempt.

Yours with an open mouth,

-B

It is impossible now to look at the sky and see blue. The sky, every morning as I open my blinds and take my first frightened breaths, is red as blood, as orange as fire, as welcoming as hell. It is a fearful time to be alive and at the mercy of small men and towering engines of malicious capital. I feel tired and the sun feels like a stranger.

People I love are being evicted. People I’ve never met are dying in the dark. My heart creaks like sailor’s ropes to hold onto anything useful. I try to keep busy, keep my head down, keep the flames from licking my ears and most of the time this works. I am going to work. I am taking my pills.

I am performing in shows like this one. I am hanging out with artists, carving Algonquin tables out of vape smoke and streetlight. Sometimes this is enough. Other times I go home, and on the Uber ride back I check my phone and send my girlfriend a single text:

Chicken emoji. Two. Moon emoji. Question mark.

Hieroglyphs in cybersand asking a simple question:

“Cock tonight?”

For the last two months we have been reading Charles Willeford’s hard-edged novel Cockfighter about a man who raises chickens to fight. It is the fourth book we’ve read together. She lives three states away and this is what we have. Cockfighter’s protagonist has taken a vow of silence, refusing to speak until he becomes the cockfighting champion of Milledgeville, Georgia.

Sometimes after a long day of living as queer women in this American crematorium we are crackling, smoking, and speechless. We don’t want to talk about her engineering degree, or my day job, or what we can’t do for everyone we love. We don’t want to talk.

Even me with my ever-bursting dam of love letters. For all my words, for all my poems, there are some nights where I am a dead child’s bedroom, full of everything but what I was made for. In those times, we read. We carve silence out of someone else’s words and burrow into the negative space. We read books.

When we first started talking, we would send each other quotes from our favorite authors, dropping passages and poems in each other’s laps like cats with twitching birds. See what I’ve found for you. See what scrap of Sara Teasdale I have butcher paper’d my heart in today. I love you. So does Emily Dickinson. I love you, so does James Baldwin. We build a glossary, big as a house, furnished with a lovers’ cant whittled out of other people’s hearts.

Now we read books. We hide in thick paperbacks like contraband. We are contraband. We are a life’s savings slipped between the pages. We could burn down tomorrow and it will be the riddle of ashes to figure out what was more important, us or the books. Both are worth crying about.

When I moved back to Atlanta all my books fell off a UPS truck. All the books I kept through the divorce were strewn across some patch of asphalt between New York and here. Some of these books were out of print. Some of these books were signed by red-eyed authors at poetry slams Some of the books were gifts from poets who are dead now. Some things can never be replaced. There are days where I remember this, and weep.

Now I build better libraries out of my lovers, reading books and keeping them safe. I hurl trashy horror novels to Vermont. I hurl terrible fantasy to Louisiana. I make my bed with short stories. I slip my books into these glamorous loves like free libraries. We all take what we need. Reading aloud has become something necessary. It is the only way I know to keep people close from afar.

Ursula K LeGuin says books are bags- are sacks- are medicine bundles. They are how we hold things that will heal us, things that we must carry to continue on. Until we see each other, books are my hands, my teeth, my fluttering throat. They are how I hold her. They are how I cradle the gargantuan ache of loving someone with a briar of busy highways between us. I read to her, she listens. She hears a story. I hear her breathing.

This is a fair trade. This is enough.

And so I leave shows early. I leave parties before they start. I cancel plans. I call a woman I love and open our book to where we left off. Neither one of us can sleep, our bedrooms are driftwood in red oceans of panic, and the sky is on fire. Who knows what tomorrow has for us.

But tonight we have something. Tonight we are a chapter away from finishing Charles Willeford’s Cockfighter.

And then starting something new.

6/27/2025

Sleeping Together: How queer love helped diagnose my narcolepsy (with video)

Sleeping Together: How queer love helped diagnose my narcolepsy

I was recently given the honor of participating in a variety show celebrating Queer Joy. I intended to perform a suite of love poems that I’d already prepared, but after reading (again) the part of Inferno where Dante encounters the lustful, and is so overcome with grief that he faints. As stomach-turningly pretentious as it is to be inspired to write by Dante, I couldn’t help myself. I abandoned my plans and wrote this piece about sleep disorders and the healing power of queer love.

Yours with an open mouth,

-B

PS. Music for the piece was composed and recorded by Mykal Alder June, a phenomenal trans musician and writer here in Atlanta. You can find more of her music at her bandcamp.

Is anything as embarrassing as falling asleep? There’s always this strange timidity to it. Whenever we hit that paradoxical drift and cliff of the world turning black and our brains just going away, it’s right there. The body becomes a vanishing cabinet, and poof, we disappear into our flesh. Dead weight. Body blankets. Sandman sandbags.

There’s no fanfare, no final bow. We are turning over the theatre to its audience of ghostlights. It’s vulnerable. It’s mortifying. Especially if you, like me, occasionally snore.

Especially if you, like me, fall asleep right before, right after, or occasionally during sex. A lot. More times than I care to admit I have literally been in someone’s mouth, leaned back, closed my eyes, and woke up to the cocked-head confusion of my lover holding me like a microphone at a press conference and asking the all-too-familiar question: “Uh…babe?”

And what can I do? How do I excuse the wandering child of my mind, slipping my hand in the supermarket and drooling in the bread aisle? Most of the time I laugh, I look guilty, I say it’s not their fault, or blame work or the weight of the world and most of the time this is enough. I yawn. I stretch. I rally and, with apologetic eyes and sure hands, I make up for lost time. And so it goes.

And so it went until one day, when my long distance girlfriend visited for the first time and in our first tender touches, it happened. Again. This aubergine shame ballet. Her mouth. My drifting body. My ink and come-to. Her incredulous smile. My nervous and trembling wait for the moment I, again, must explain this strange and unforgivable quirk and she says it.

“Oh, sure. You have cataplexy. My ex had that.”

And suddenly it was there proud as a patch on a Girl Scout sash. I wasn’t a disaster or disappointing. I was diagnosed. I had a thread to follow, a spindle to the exit. This impossibly cool punk rock Ariadne had given me a way out of the labyrinth. No more bullshit. Not only did I have something, but someone else had it, too. Someone worthy of her love, if only briefly. And so I looked it up. Turns out it’s not quite cataplexy, but I have it narrowed down to two:

Either I have a rare form of narcolepsy called vasovagal syncope or I have a rare form of cataplexy called orgasmolepsy. Either sex short circuits my vagus nerve until the feeling pulls me under, or the intensity of sex suddenly makes me lose so much muscle tone that I’m awake, but briefly catatonic. Either way, fucking is so much sometimes that my body shuts down until I come gasping back to the world minutes later.

Once my condition had a name, I felt a wave of euphoria. I faint because love is too much. I am a Bridgerton plotline. A Jane Austen stuntwoman. I am a corseted hypoxia. I am swoon and sudden rush. I am blush and oblivion. I am fanning myself with the vapors like a fine Southern Belle, all weak ankles and only your arms can save my fine china face from the floor. Catch me, carry me across the threshold, put me back in the cabinet with all the other beautiful, breakable things. I am every woman’s secret dream: a romantic cliche.

And how appropriate this woman was the one to name it. How appropriate for this girl off of Grindr to know me like this. This is what Queer love is all about. We drift through the world impossibly alone, always looking down until our eyes touch a pair of scuffed Doc Martens and a woman brighter than the sun takes our hand and whispers “me, too.”

We all feel so alone until we don’t, don’t we? We all feel so zoo animal and freak show, so singularly weird and broken until we meet each other. Until she likes the same music, until they’re wearing a T-shirt of that one movie you love. Until it asks you to punch it in the stomach as hard as you can. Until he kisses you and begs you not to hold back this time.

I once told a cis woman I couldn’t hook up with her anymore because my body was changing in ways that frightened me. I once told a girlfriend that I needed sex to be a little more forceful, that I needed to be taken, like a fussy child to the pool.

I would have fun once I was pushed in.

She smiled like she could already feel the water at her waist.

To be known is to be loved. To be othered with one another is all we can hope for. Tie me up. Spit in my mouth. Wait for me to put on my fursuit. We meet each other in such strange and beautiful places. We make eye contact in candlelight waiting for the wax to get hot enough to mean something.

I told my girlfriend that, sometimes, I fall asleep during sex. She gave it a name. She held me. She leaned me back onto the bed and asked me with stars in her eyes:

“Can I still touch you…after you’re asleep? I’m…kind of into that.”

We find each other, don’t we? Questions and answers, calls and responses, songs and choruses. Swapping our dark idiosyncrasies like every night is Christmas morning. She knows I fall asleep. She’s into that.

God. Isn’t it hot? Isn’t it all so enormous?

Someone wake me up.

I’m falling in love.

6/12/2025

Public Indecency: 36 Views of the Atlanta Fringe Festival

Public Indecency: 36 Views of the Atlanta Fringe Festival

There’s more lingerie in my laundry than anything else today. It feels like a dinner table littered with the bones of a beast. It feels like a box of pizza rattling with crusts on its way to the trash. I ate my fill, and now there is just the mess.

For the last two weeks I’ve been performing a one woman show as part of the Atlanta Fringe Festival, a local chapter of the massive celebration of independent and off-kilter art. The show, 36 Views: A Story of Tits and Poetry, was a nonlinear memoir of my transition filtered through the prism of my tits, in thirty-six vignettes, styled after the woodblock print works of Hokusai and Henri Riviere. Riviere was so inspired by the Japanese master that he made his own tools to pastiche the ukiyo-e style. The show was my attempt at making my own tools as well.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribed

The work, the poems that I started two years ago, was initially planned as a book. When I noticed that all my Atlanta artist friends were talking about the Fringe Festival, I looked at the closest things I had to a coherent piece. I pitched my suite of tit poems. I knew hundreds would apply and the lottery system meant my inevitable rejection wouldn’t be personal or based on merit. I could grouse around with all the other unluckies in my friend group and watch the lucky ones who got in.

Then I got in.

And I had to convert my book of quiet poems into a stage show. I had to figure out a way to play a Bach prelude on a baby grand and make people forget cellos existed. I had performed poems before, but always as part of a larger show of disparate elements. Amongst burlesque, magic, and religious-themed drag, I was a brief and essential jet of calming air in a heady jungle climate of the debaucherous night. I was on stage for seven minutes at a time. Now I was responsible for forty. While my friends could play guitar or dance, I had my titty poems, time, and a microphone.

This began with maybe a slide show of paintings inspired by the poems, or maybe commissioning music to live underneath my words, or maybe interactive elements, but every time I considered a new element, it felt hollow and insufficient. Inevitably I did what all self-respecting artists do in the midst of creative crisis: I whined to my girlfriend about it.

She sighed and repeated the same maxim she always did, one I’ve heard often enough to recite along with, but one I never tire of hearing:

Art is a process of amputation.

This show was about connecting, about translating an experience and bringing people in. Pyrotechnics would only push them away. But how? What would I cut away?

Then I remembered those nights around burlesque dancers, and an idea formed. If I wanted these poems to feel transgressive, intimate, and immediate, I would need to put some skin in the game. I would take the quiet, private joy of wearing lingerie for my girlfriend and bring it to stage. As pieces of paper would fall from my podium, I would lose layers of clothing, until finally I would recite my final poem bare-breasted and invite the audience in. This show was about getting naked. I would have to take that literally.

Making a solo show is solitary work, just like writing poems. I would sit in my bedroom and arrange pieces of paper, tetris-ing blocks of poetry into new sequences and recite them to the empty air. It felt isolating. Even the comradery of my fellow Fringers and their processes had a hermetic distance to it. We were all nervous test-takers with our shoulders over our papers.

It left me wholly unprepared for the social explosion of the festival itself, bumping shoulders with over sixty performing acts, meeting traveling artists from as far as Wichita, Kansas and Anchorage, Alaska. Suddenly puppeteers were asking about my poetry, I was asking improv comedians about the drive down from New York. I was eating pizza in restaurants past closing. That click-cracked soda can feeling of all that was sealed away suddenly bursting out bright as Amaterasu from the cave. I am reminded, with a smile, that the sun was lured out with a bawdy strip tease from a literal goddess of revelry. The laughter of the gods shook the world.

That’s what these festivals feel like. From the national Poetry Slam events from my youth to now, it feels like the laughter of the gods after the dark of a shameful cave. I saw so many different and wonderful kinds of performance. I learned to trust my own. That’s the magic of these spaces. Improv comedians, noise guitarists, clowns, magicians, and playwrights, all brought their talents to bear on bars, theatres, streets, and art spaces across two weekends. I made a point of seeing the shows of other trans perfomers and marveled at how different our stories were.

My tit poems were different. They were enough. Performing them for audiences, casting their sheets of paper into the air to hit the stage floor like poisoned seabirds after each reading. I felt reinvigorated. I felt a kinship with these poems I’d admittedly gotten a little sick of. Connecting with my audiences, with my stage crew, my venue manager, and the other performers in my venue reminded me why I write these poems to begin with: to connect. I am trying to paint my experience. I am trying to translate the joy and despair, the uncertainty and terror, the spiritual ecstasy and godless abandon of being trans in these tumultuous into a language others will understand.

When I finished my first performance, a trans woman stopped me in the lobby and told me that my show made her feel “seen.” When I finished my third, my mother hugged me and told me she was proud of me. I felt seen, too.

Fringe was gathering of misfits and freaks. It was a parade of people like me trying to turn their strangeness, their vulnerability, their obsessions, their enormity into a beauty that connects. My tit poems began as moment where I felt completely alone with the enormity of inspiration. I was surrounded by a family that would not understand why a picture of the Eiffel Tower made me sit down and cry.

When I got home from the final performance of my show, I peeled away my last pair of nipple pasties. They pinched my skin before they let go. My show ended with a small private hurt in the dark of my apartment. After all the noise and color and light and wonder of two weeks spent hurling my veins to strangers’ hearts, I was left with this private moment. I looked down at the pastie. I looked down at my stinging breast. It hurt. But the hurt was worth it.

I smiled to myself. The hurt always is.

Yours with an open mouth,

-B

PS. I want to amend this letter with a vociferous thank you to the team behind the Atlanta Fringe Festival, who were endlessly patient and kind as I neurotically rocketed through this process. Thank you Executive Director, Diana Brown, Marketing Director Chris Alonzo, Production Director Nadia Morgan, and the amazing staff and crew at The Supermarket, who made this thing I scarcely dared to dream into a dream come true.

5/7/2025

Art, Solitude, and the Comfort of Secret Projects

Art, Solitude, and the Comfort of Secret Projects

I stopped updating my blog during National Poetry Writing Month. I abandoned my daily writing practice twelve days in. I found myself pulled towards other pursuits like Jiu Jitsu, my penance, performing, and enjoying the improving weather. Normally, April is an explosively creative month for me. I am trying desperately not to take too much stock in how different this month has been.

Our country is in shambles. It’s been hard to enter the same headspace I wrote my previous work in. The ecstatic joy of my transness is changing into something cooler, more pensive. I write now and read back things that are steelier, angrier, less aglow with the orange light of new flame. Things have been burning for a while. This spring I’m performing a one woman show celebrating the work I’ve been doing for my “tit poems” project. A part of me is excited to perform. A part of me is excited to begin the process of closing the book on that phase of my life.

And yet I still feel the spark to create. I still like making things. I still like writing. I find myself wondering why poems did not come to me, did not sit on my fingers and at my feet like the birds and beasts of St. Francis. Throughout my time in prayer during Lent, I’m slightly embarrassed to say that I occasionally had an audience, whether hosting out-of-town lovers or local ones, I had to excuse myself to whisper my thoughts to God and hurt myself according to our pact.

There were times I tried to pray aloud, but it never felt right. It felt like performance. It felt like posturing. My nightly prayers were for solitude. God could hear me. That was all that mattered.

I think I needed to be reminded of that. I think I needed to learn again to pray silently. To write silently. To create silently. To shut myself away and hammer in the dark. There’s a Tom Waits song on the album Mule Variations called “What’s He Building in There?” In the voice of a mounting neighborhood paranoia, the song speculates about the sinister secret machinations of a reclusive neighbor.

What's he building in there?

What the hell is he building in there?

He has subscriptions to those magazines

He never waves when he goes by

He's hiding something from the rest of us

He's all to himself, I think I know why…

As I ponder solitude, I think about the song again. Differently this time. Rather than one of the concerned neighbors strolling by the perfunctory “spooky house” with its “spooky neighbor", this time I think of the Builder. Did the rumors bother him? Did it hinder his process? And then it hit me. As long as the neighborhood didn’t know what he was building, he could be building anything. Composers will sit at their pianos all alone, but the song is no less itself in their ears as it is blaring out of my iPhone while I cook dinner.

One of my favorite writers, Kevin Killian, wrote heartfelt, gorgeous reviews and stuck them, like prayers in the Wailing Wall, into the dross of Amazon dot com. My artist friend Sam is on pause from commissions to learn how to love her own processes again. My boyfriend refuses to tell me his handle on Ao3. My girlfriend insists on posting her own writing online without tags to make it harder to find. They build in the garage with the big door rolled closed. They carve their names on the support beams before the foundation is poured. They pray quietly.

Lately I’ve been hungering for that. I want to hide from the neighbors.

And so I have taken up some secret projects. Small, embarrassing stones I will worry into effigies with nothing but time and my tongue. Frivolous, serious, who cares? I think there’s something worthwhile in yearning for a peace with one’s own creativity. To discover the inner critic and find her smiling. Peace can be achieved. It can be cultivated like moss in dank caverns, in dark, blue solitude.

In Patrick Suskind’s Perfume: Story of a Murderer (a book I reference so much it may as well be an implied silent quotation in every essay), the villainous Jean Baptiste Grenouille retreats to an underground fissure in a mountain for solitude. While he is there, his entire existence is put towards moments of memory.

“The setting for these debaucheries was—how could it be otherwise—the innermost empire where he had buried the husks of every odor encountered since birth.”

This time in the book means the world to me. I find myself returning to it over and over. I think because I covet it. Not just the characters supernaturally acute sense of smell (a dark mirror for my own anosmia) but his complete satisfaction with being alone, with creating alone, entirely in his head. I want that kind of gentle, dreamer’s peace. I want cathedrals of vapor to be enough to walk through with no one but God and my own soft shadow. I want to make things and feel the simple hitches and hallelujahs of failure and success all my own. I want to make with no audience in mind.

Last weekend I was offered the rare pleasure of reading to raise money for a literary magazine. I had made plans, had picked out my poems since my invitation weeks ago. I was going to read tit poems, to promote the upcoming book and the show at the end of this month (more on that in another post). But as I was assembling my reading packet in the days running-up, I found myself drawn to other work, newer work, angrier work. I called my girlfriend about it in a state of mild crisis (bless her patient and tireless love) about this and she told me simply enough:

“Baby, I mean this with love, fuck the audience. Do the ones you want. This is for you.”

And, when I think of her, and her buried treasures in the glittering deserts of the untagged internet, I know she understands some small part of that peace in Grenouille’s cave. I know she has felt the stares of neighbors licking her neck as she slammed shut her shed doors. I know, no matter what she was building in there, it was for her.

Spurred on by her advice, I changed my lineup. I read the pieces I wanted to read and they went over better than I could’ve hoped. Honesty and vulnerability honored. Listening to my own echoes in the cave guided me to light.

And so, I will send off this Spring with a kiss. I will perform for an audience. I will bare my soul and my breasts under a spotlight with a smile, but then. But then. But then, dear friends.

The next thing I build will be just for me.

Yours with an open mouth (and a locked basement door),

-B

4/8/2025

Psalm 33:3 and the Need for Noise

Psalm 33:3

There’s a line from Randy Travis’ “Forever and Ever, Amen” that always gets me. It’s in the chorus, where Travis playfully tells his girl that he will love her:

“As long as old men sit and talk about the weather. As long as old women sit and talk about old men.”

Delivered by the molasses-slow candy-sweet carousel of Travis’ voice, the line has a homespun hypnotic charm. It’s so simple and earnest. It encapsulates why I like Randy Travis (and why, long before my return to church, I put “Three Wooden Crosses” on repeat more times than I care to admit.) It paints a specific image.

I’m immediately flung out of the song and its charming folksiness and I’m sitting with a circle of gossiping women. I am holding a pale pink teacup and listening patiently as my friend tells me about her no-good husband of fifty years. It’s such a pleasant daydream I can’t help but smile.

And then I can’t help but think of the eternal talk of my own people. Trans people. What do we gather and gossip about? Lately, perhaps it’s the thundering arrival of Spring, but everyone in my life seems to be starting or joining a band. Virgil has recommitted himself to the bass. Emily is talking about starting a noise project with her friend. V is more seriously pursuing DJing. June is releasing more songs despite a looming deadline for her one-woman show. After a long hiatus from writing poetry, I find myself back and reinvigorated going into National Poetry Writing Month. Whenever I perform lately, the call to add music behind my words continues to swell. We want, it seems, to be making noise right now. More than ever.

For Lent this year I’ve been reading the Psalms every night as part of my penance. The Psalms are reportedly the prayers of Christ as well as the lamentations of King David and the exiled Israelites. It’s been rewarding to root myself in the words of my Savior as I travel with Him in the desert. The lion’s share of the Psalms are attributed to David after he was exiled from Israel by Saul. Despite being a warrior, redeemer, and anointed King, David was first discovered playing his harp for his flock. He is a musician, a poet, and when he is at his lowest, he sings to God.

In Mike Flanagan’s Catholic-soaked supernatural horror miniseries Midnight Mass, a priest on Ash Wednesday offers a sermon:

“Do you know what Psalms are? They’re songs, from the Greek psalmoi. It means music. Songs of prayer. Songs of praise. That’s who we are. That’s who we must be. That’s what it means to have faith. That in the darkness, in the worst of it, in the absence of light and hope, we sing.”

King David sang to the ends of his enemies, to his own rescue, to his own reunion with the full favor of God. It mirrors the other context for the Psalms: the Israelites’ lamentations in the wake of the destruction of their temple by the armies of Babylon. A cursory walk through the Psalms becomes a thicket of tears and despair, of abandonment and longing. I can’t help but feel the heartbeat of my trans kin in these words. We sing. We all want to sing right now.

We want to reverse the fall of Jericho and build up a walled city of sound, mortared by our tears in exile. We want safety and so we sing for it. Lent is a time for community and much as it is for isolation. My Ash Wednesday began with a text from my girlfriend. A screenshot from Tumblr of someone answering the question “Thoughts on Lent?”:

God said he was going out to the desert for a few weeks and I’d hate for him to go alone.

And isn’t that it? Isn’t that what we’re all hoping to do with our noise?

In the documentary Blackfish, a trainer recounts how the park’s executives decided to separate a whale calf from its mother. When the calf was finally removed, the normally quiet whale mother isolated itself to a corner of its pool and cried endlessly, howling in ways the trainers had never heard before. When research scientists came to analyze the cries, they determined that the new cries were specifically long distance cries. The whale was trying to reach beyond its own reality to its calf.

Every noise I make now as an artist feels like a long distance cry. To God, to reason, to the distant clouded kingdom in which my existence is not a talking point. I am reaching out, loudly, to crack the mirrored glass of the world and touch something brighter than myself. I want to touch to play the secret chords and feel the favor of God. I want to find the quiet in my noise that I find in prayer.

The other part of my penance is the anachronistic practice of self-flagellation. I whip myself, one lash for each verse of the night’s psalm. On some days this means five or six lashes. On other days it can mean fifty. I never let myself read ahead. I accept each day’s pain as it comes. Again this is about connection. Connection to the suffering of Christ. Connection to the suffering of my people. Connection to my body as those in power seek to threaten it. I whip myself to offer God my flesh, a prayer of thanksgiving for the moment when I heard His voice. When He told me the truth of my body. When He told me my name. For the truth of my flesh, I offer my flesh. For the truth of my name, I pray in the name of His son.

As my trans friends and lovers tell me about their bands, their practices and projects, I hear the new hymns of my people. As I look at the pictures of my welted back, I feel the calligraphic prayers of His will on my skin. I listen to their new songs. I tell my friends about their bands, share Spotify links and Bandcamps. I look up keyboards for sale online and wonder if today is the day.

I think of David in Psalm 33:3 telling us:

Sing unto him a new song; play skilfully with a loud noise.

More than anything, when I hear the music of my people I turn it up. I scream. I think of the song “Punk” by The Duende Project:

When they looked down on you

and they said in one faint, sweet voice.

“Hey you kids that shit’s too loud!”

And you screamed right backNO

SUCH

THING.

I am loud tonight. I am a king with a harp. I am a walled city. I am a desert of faint music. When my Savior was in the desert and there was no sound but the devil. I bet He sang. I bet He refused to be quiet. I bet to Him, there was no such thing.

When you are naked in the desert, the only thing you carry is your voice.

In the right kind of quiet it can carry for miles.

If you’re loud enough.

Yours with an open mouth

-B

3/22/2025

If You’re Not Vincent Price, I Will Not Remember Your Birthday

If You’re Not Vincent Price, I Will Not Remember Your Birthday

The hardest part of potentially leaving Facebook after Meta decided people like me have had it "too easy lately" was losing all the birthday reminders. I ultimately couldn’t give up knowing the most important days of people’s lives. I am a coward.

I am also bad at birthdays. Right now, if you held a gun to my mother's head and demanded I say her birthday out loud...I can at least say with certainty when her death day will be.

I can't hold anyone's big day in my head to save my life.

Except one.

Every May 27th and October 29th I try to cook something special and watch Theatre of Blood starring Vincent Price. October because that's my birthday. May because it's his. May 27th, 1911. Died in 1993. I know that because it's tattooed on my forearm. I know it because it's on the back of his picture in my wallet.

I know it because there are still nights where I can't sleep until I listen to his Colorslide Tour of the Louvre.

I know it because if any of my younger friends, God be with them, ever says "Who's Vincent Price?" anywhere I can hear it they will have to cancel their plans because they are about to learn.

Well, he's an actor. And a bi icon. And a certified Scooby Doo special guest star. And a gourmet chef. With his own cooking show. And cookbook (which I own). And an art collector. Who donated his entire collection to Sears for reproduction rights because people, he said, deserve to have fine art in their home for whatever they can afford.

He's also the man who got me into movies. Who taught me to be brave.

When I was ten my whole family moved. It was big, it was scary, and back then I was famous for being scared.

I had to be escorted out of a symphony because "In the Hall of the Mountain King" made me cry and piss my five-at-the-time-year-old pants. I had to be banned from rehearsal when my sister got cast in A Christmas Carol because I couldn't stop screaming after Jacob Marley read his lines one time, in jeans, giving it, in retrospect 20%. The idea of watching a horror movie for fun was like skydiving with my eyeballs.

But then we were moving. And my dad set up the satellite TV first thing so my sister and I didn't drive him or the movers crazy. And it was Vincent Price. And he's about to stab a guy with a spear and he's wearing a scary helmet and he's quoting Shakespeare but something about his smile makes it all seem okay.

And it was.

And suddenly I had nothing to be afraid of.

Not the symphony. Not Christmas ghosts. Not even the older boy next door to my old house. The one who did things to me at a sleepover. The one who gave me a secret and a reason to jump at every little thing.

But we had moved away, and away from him. And Vincent was on the TV saying it was going to be okay. And I believed him. I trusted him. Even after he killed a theater critic's dogs and fed them to him while quoting Titus Andronicus if you HAVEN'T SEEN THEATRE OF BLOOD YOU ARE MISSING OUT.

I let this man reach across time and hold my hand through the horrors of growing up. He's been with me ever since.

Now a lot has changed since I was a ten-year-old boy. I like cauliflower now. I have a job. I'm divorced. Oh, and a woman. But every year it's still me and Vincent.

Every year, twice a year, it's still Theatre of Blood on the couch in the dark as I quietly let go of another 365 days. Every year for my birthday I give myself the gift of that movie, that moment, that quiet unspoken assertion that everything will be okay.

It may feel like a horror movie out there. It may feel like you are a monster running from a village of torches through the wilderness of a black and white night. It may feel like the credits are gonna roll on this thing at any minute.

But it’s there. In the corners of your eyes, curling up like a well-manicured mustache, itching like a new tattoo. As I live amidst every waking nightmare of being alive right now, I know that every birthday he'll be there to remind me I made it this far.

And I better see him again next time because Theatre of Blood is just that good. It’s worth sticking around for.

And so am I. And so are you. So are all of you.

And so is life.

And on your birthday, a gift like that, funny enough.

It's priceless.

Yours with an open mouth,

-B

3/8/2025

Elihu Tells Us It’s Raining

Elihu Tells Us It’s Raining

I don’t exactly know when my life became so religious. Suddenly all I can write are homilies and prayers. It’s strange, but honestly I’m just thrilled to be writing.

Anyway, the queer bible study group I go to finally finished our discussion of the book of Job. After weeks of sitting with this man and his friends, weeks of listening to those friends bombard Job with their rationalizations and impassioned defenses and accusations about deserving, we finally reached the end. This had been my first close reading of Job, and I was stunned by how relatable it was.

When I first joined the group, it was last year in the aftermath of the hurricane that ravaged North Carolina. Now, as we conclude the story of the troubled man of Scripture, the world feels as set against trans people as it did against Job. It feels like those early chapters, wherein every verse is more bad news. His cattle, his children, his house, his health. My rights. My access to healthcare. My dignity.

When his friends saw Job, they tear their clothes and sprinkled dust on their heads. Then, they sat with Job in the ruins of his house and took turns interrogating the harried, grief-stricken man, searching for any inferiority or cause for his suffering. This is the lion’s share of the book: Job’s friends performing their grief and searching for ways to make this his fault.

Yesterday, my state passed a slew of anti-trans legislation, some of which had Democrat support. One of these senators shook my hands two years ago and told me they would always be here for the trans people of Georgia. When it came time to support the most vulnerable among us, she wrung her hands and chose politics over her supposed “morals.” Watching her defend herself, defend her decision to abandon her principles, I felt like Job. I watched my “friend” say everything but what I needed to hear. I watched my “friend” try to justify why the engines of trans marginalization would run unopposed.

Eventually, after hours of Job’s three friends’ moralizing, the youngest of their number finally spoke up.

How great is God—beyond our understanding! The number of his years is past finding out.

He draws up the drops of water, which distill as rain to the streams;

the clouds pour down their moisture and abundant showers fall on mankind.

Who can understand how he spreads out the clouds, how he thunders from his pavilion?

See how he scatters his lightning about him, bathing the depths of the sea.

This is the way he governs the nations and provides food in abundance.

He fills his hands with lightning and commands it to strike its mark.

His thunder announces the coming storm; even the cattle make known its approach.

When our group read that aloud on our uncomfortable polyblend couches of our church reading room, I was ready to chuck the book against the wall. Of course, God’s will is beyond Job’s understanding. Of course it is not his fault. It’s nature. It's the weather. The world, the cruel machinations of idiot men and bigots that pelts people, they are a new kind of weather. Suddenly every single one of Elihu’s rhetorical devices revolved around rain and storms. Every example. Every metaphor.

And then, finally, Elihu went quiet and God finally spoke to Job:

Then the LORD spoke to Job out of the storm.

Then it hit me. Then it crashed into me right out of the sky like a hailstone from the heavens. It’s raining. It’s not “a storm appeared and the LORD spoke.” In the story of Job, in the ruins of his broken house, surrounded by well-wishers and head-scratching moralizers, it’s raining. Elihu is pointing at storm above them. His message is not one of deference or humility, it’s about the futility of trying to reason with weather when it’s raining.

You have to get out of the fucking rain.

As anti-trans legislation and rhetoric reach a fever pitch, I see so much discussion of how wrong it is. When the executive order defined female as “a person belonging, at conception, to the sex that produces the large reproductive cell,” and a million well-intentioned liberals snarked about how we’re all technically female at conception, I felt it raining. When people bring up the hypocrisy of Republicans’ fetishizing of parental choice for school vouchers and not health care for their trans children, I felt it raining. Finally, through Job, through Elihu, I had something to do.

No matter what rhetoric or justification they come up with, it’s just weather. I will no longer argue with the weather. The storm of fascism and idiocy will undo itself against the earth. Their rain will end. Until then I will be focused on shelter for my people. I will be focused on keeping the trans people I know happy and safe.

Job’s mistake, Elihu points out, was wasting time trying to understand God during a thunderstorm. It’s a mistake you can’t afford to make covered in boils and the ashes of your home. It’s a mistake I’m tired of making.

So when Elihu tells us it is raining, I’m tired of sitting around with those who would seek to explain it away. I’m tired of people who have answers but no umbrellas.

I will not entertain “discussion” until my people are dry.

1/31/2025

Night Teeth: Cute Aggression and the Grief of the Afterlove (with Video)

Night Teeth: Cute Aggression and the Grief of the Afterlove (with Video)

I was kindly and graciously invited to participate in an evening of Poe-inspired performances recently. While others danced and sang, I got up as usual with a monologue/essay/poem thing, this time fueled by the oft-forgotten “Imp of the Perverse.” Rather than rely on the self-destructive impulse of man, I focused on another subconscious urge: cute aggression.

While the piece started somewhat as a joke, re-rigging a classic Poe story to be about biting my girlfriend, it has now become strangely important to me. The naked panic of the piece’s back half still makes me somewhat uncomfortable. Fear doesn’t show up in my work often in the way it does here.

If you’ve ever felt the urge to bite your lover, this piece is for you.

-Recorded and Performed in the Poe-Sessed show at Atlanta’s Redlight Cafe

It's 2:53am and I'm in a Philadelphia hotel room with my girlfriend. It's the day after Christmas, our first Christmas together, we are full of Chinese food, and I should be asleep.

But I'm not.

Instead I am watching her sleep. She's so peaceful, on her back like a portrait of Ophelia surrounded by the flowers of our stained hotel sheets, halo'd like a saint in her own messy hair. She is, I swear to God, smiling just a little, like she still dreams like a child. I watch her breathe, building every slow, snoring exhale in her chest like a ship in a bottle, piece by meticulous piece. She is perfect. She is defenseless.

And I want to bite her so bad my teeth are aching. I want to bend my mouth to her bare chest and pull pieces of her away like Autumn leaves as she gives in to the Winter of sleep. I want to snow angel our bed with red wings and gnaw her shoulders like I am an animal held fast to the trap by her limbs. Like I'm a trapped animal.

I am a trapped animal.

I am a contortionist bent into a box of contradicting instincts. I am wrong. I am sick. I see my sleeping and unguarded love and want to shred her body like kindergarten snow. I want to hurt the person I love.

But maybe that’s everyone.

I mean, don't we all see a baby and crook our fingers into pincers? Don't we all see a masterpiece and imagine putting our hand through the canvas? Don't we all see beauty and clench our fists?

It is a phenomenon called cute aggression. When something is so perfect and adorable our brains cross the wires. We love so hard it hurts a little. Like we know these things, these soft glowing great parts of life are too small and precious to really belong here. Like our fingers are red pens so rapturously ensorcelled by a book we have to edit it.

It is a heaving perversity held aloft on wings of love. We love things, and want to squeeze them to death.

Cute aggression is a common form of dimorphous expression. A kind of emotional hyperbole where our joys become so great we have to skip right to the ways they will hurt us, just to stand in the same room with them.

I am, on this cold christmas night, reassured by Google that I don’t really want to kill my girlfriend, that I’m not a monster, that I can sleep beside her without waking up with her blood in my mouth. I roll over, lay down, and try again.

But still, no sleep. Something about the tidiness of it doesn't settle. The urge to bite my girlfriend feels immediate, urgent, percussive inside my skull. It feels all consuming and massive and everything but cute.

She's not a baby. She's not a bunny rabbit. This is not cute aggression. This is something else. There's a taste in my mouth from all the way down. It's sour. It's sharp. It's metallic.

It's fear.

Watching her sleep, watching her breathe with all its mechanique, I can imagine the moment the machine breaks down. Underneath her breath, I can hear her not breathing. How many great loves are ended by someone dying in their sleep?

I think about biting her because I can imagine the moment she wakes up, barks high and clear as an EKG. I want to bite her in her sleep in case she doesn't wake up. I want her to feel pain as much as I can to atone for the moment she can no longer feel anything. I want her to hurt before she can’t anymore.

Because love hurts. It pulls your eyelids back and bids you look beyond the veil of tears at the griefful void of the afterlove. It is looking at your dog and imagining the last quiet trip to the vet. It is the shadow past the sun.

Here is the precious thing, it says, walking her up the aisle to me.

Here it says, leading her away, is what it costs.

It is an ulcerous pain to contend with love’s ending at the corona of its every kiss. I am so scared of any moment on this Earth we do not share that my brain graffitis every tenderness with torture.

Nothing keeps you in the moment like pain. Nothing keeps you present like teeth in your side. In order to reassure Thomas that he hadn't lost his Savior, Jesus first had to show him a wound. I need to wound her hard enough that life won't kill her instead.

It is the impulse that sees sickness and thinks of sharp instruments. It is a surgeon's lust. I need to see her insides to know they are still working. For as long as we have known illness, we have tried to solve it by cutting each other. I am groping with my mouth full of scalpels to save her. If we are biting each other, we are not losing each other.

She is my sleeping feast. I am her lockjaw lover terrified of starving.

I lean down in the flickering dark and kiss her forehead. My teeth are a riot of want in my mouth but I hold back. I whisper sweet nothings in her ear.

She wakes up.

She groans.

And she bites my hand. Hard.

Like she’ll never let go.

1/14/2025

The Epiphanies of Impossible Women:

Tokyo Godfathers, the Virgin Mary, and Trans Nativity

The Epiphanies of Impossible Women: Tokyo Godfathers, the Virgin Mary, and Trans Nativity

The last flickering light of Christmas just blinked gracefully out, and like all good, fading lights, it portends a journey.

Last week was the Feast of the Epiphany for good Catholic girls like me. It’s meant as a commemoration of the final triumph of Christmas: the visitation by the Magi.

Given its proximity to presents and my participation in things like "nativity plays" through my church growing up, the Christmas story has always been ubiquitous, but this year it hit me in an entirely new way.

This particular bout of faithful introspection was triggered by my mother, letting me know that she and my sister just sat down to watch my favorite Christmas movie: Tokyo Godfathers.

Directed by iconic anime director Satoshi Kon, Godfathers has unexpectedly superseded Satoshi Kon’s other famous work, Perfect Blue as my favorite movie of his. Set on a frosty Christmas Eve in Tokyo, the film follows three homeless people (Gin, a paternal drunk, Miyuki, a tough, streetwise teenager, and Hana, a theatrical trans woman) after they stumble upon a lost infant child.

As they stumble through a night of intersecting pasts, yakuza bosses, violence, and tears, the group reconcile with each other, their lives on the streets, and their miraculous new infant in tow.

And, of course, I am drawn to Hana, the caterwauling and kind-hearted woman of the trio, who jumps to conclusions, invokes providence, and demands better from her friends while sprinting away from her own traumatic past. Casting a trans woman as one of the Magi gently asked me to consider our role in the Christmas story. Where were the women like me? Was there room for us, even in the stable among the animals? And then I found it.

In the gospel of Luke, when Gabriel appears to Mary to announce the Good News, it is a trumpeting of pomp and bombast, festooning the portended babe with titles like Son of the Highest and proclaiming:

…he shall reign over the house of Jacob forever; and of his kingdom there shall be no end.

Mary's reaction is not joy or awe or fear. She asks a question:

How shall this be, seeing I know not a man?

And the angel explains it simply enough, that she had been visited by the Holy Spirit. Her pregnancy is a miracle. And then he says it, my favorite verse in the whole big Bible:

For with God nothing shall be impossible.

Mary responds with her usual steadfast humility.

Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word.

There’s a crude joke in the transfemme community: “Just because we can’t get pregnant, doesn’t mean you can’t try.” When I think of Mary, similarly faced with her own biology, I can’t help but think of the joke. The virgin. The trans woman. We both can’t get pregnant, but that doesn’t mean we can’t believe. It doesn’t mean we can’t try.

Mary accepts the miracle, accepts the baby in her untouched womb, accepts her role in changing the world. Then she does what we all do: she tells her cousin, Elizabeth.

Only to discover that Elizabeth has recently been blessed with her own miracle. Barren in her old age, she was given a child again by the Holy Spirit. When she saw Mary, her babe leaped in her womb.

And she spake in a loud voice: Blessed art thou amongst women, and blessed is the fruit of they womb.

And there you have it. The great beginning of salvation. Two women talking. Two women who chose faith over the facts of their biology. Mary, the suddenly pregnant virgin. Elizabeth, the once-barren expectant mother. In God nothing is impossible.

I know that joy. I know the hot light of God whenever I talk with another trans woman. That rapturous moment of appraising our changed bodies, our newly minted euphorias, and looking at each other with eyes that ask, humble as Mary:

Can you believe it?

And I suddenly find that I can. I can believe in my body, born a man, forged in coarse puberty, hardened into a life of depression, suddenly and slowly reborn into glorious femininity. I can believe that God knows me, that my transition is done according to His will.

Behold the handmaid of the world. Be it unto me according to thy word.

I, too, am one of God's impossible women. I am blessed. As we near inauguration day and my state continues its almost gleeful restriction of trans rights, I have to remind myself of these blessings. I have to remember that in Mary and Elizabeth’s time, their world was also set against them.

Mary feared for her life as an unmarried woman with child. If Joseph hadn’t stood by her, the Son of God would’ve died with her, put to death for adultery. The first thing the couple did after accepting the good news was flee. They did what they had to do to survive a world that would hurt them.

And then, of course, there’s the Magi again. I never paid much attention to them before. Three men that saw a star, followed it to a baby, gave those three gifts that seemed like the worst things to give a baby (what kind of baby wants “myrrh?”), and then left. And then I went to mass, and my priest offered more context.

Herod, fearful of being usurped by the rumored birth of a new King of the Jews, ordered the death of every two-years-old-or-younger male child. This stains the entire kingdom with innocent blood and the madness of a small men desperately clinging to his power with the chipped tip of a sword.

When the Magi announce their intentions to Herod, to seek audience with the new king, he asks them to return and send word to him, so that he can worship as well. As soon as they see the Christ child, however, they decide not to. They go home by another way and leave Herod in the dark.

The Magi witness a miracle and decide to protect it from a tyrannical regime, from oppression, from death. They are led to Bethlehem by the stars and led home by their consciences. As things continue to intensify in my state, I look up and see the shadows of Herod in the stars.

I see the impossible women around me. I see the long journey towards our salvation ahead. I see the stars. I see a king who would put us to death to preserve his own power.

I see hope. Even in the cold. Even as bitter evidence of climate change melts all around after the largest Atlanta snowfall I’ve ever seen in my life.

I see us. In the greatest story ever told, I see us. I see women sharing in joy, and I see God in us and I smile in spite of everything.

“For with God nothing shall be impossible.”

Nothing.

12/21/2024

Drowning in Coats: 2024 in Review

Drowning in Coats: 2024 in Review

2024 is closing its great, heavy eyelids. This vast and impossible giant of a year, its great belly swelling and shrinking with each dwindling breath, lays before me. I can truly say this creature has exhausted, delighted, saved, and slaughtered me so many times over. When I say my friend and fellow writer June recount her year’s creative undertakings, I decided I needed to pay my own respects.

It’s hard to believe that it was only January that I managed to publish my first poem under my name. A love letter to my girlfriend’s top surgery scars, “Untitled” was a fitting omen for the year ahead. I had fully and truly fallen back in love with poetry, writing as much as I could. I also started performing as much as I could. To that end, let’s get into what I got up to this year.

Write Club ATL

I was invited by my friend to participate in this staple of Atlanta’s live lit scene. Throughout the evening, writers are pitted against each other and given diametrically opposed prompts (Hot vs. Cold, Come vs. Go, etc.) and the victor is determined by applause. I was given “Boil” vs. my opponent’s “Simmer.” I took it as an opportunity to write about Phlegethon, the boiling river of blood from Dante’s Inferno (and, in turn, write about violence, transness, love, and the rapidly expanding transphobia of American politics). Performing an essay live in front of such a responsive audience was an incalculable joy. The joy was apparently mutual, as I returned home with a tiny trophy and an invitation back this month. Now I have two tiny trophies.

PUBLISH US & Hundred Pitchers of Honey

In the new year I wanted to pursue publishing. I felt like I had enough of a backlog and enough confidence in my writing that I could return to something competitive. To that end, I took to social media. Around March and April, in anticipation of the National Poetry Month challenge, I reached out to a mutual for mutual feedback and accountability. We decided to start a discord group and invite some more friends. Now the PUBLISH US discord is going strong with four members desperately trying to keep each other sane. We were colleagues at first, but then we were all invited to read our pieces in the Hundred Pitchers of Honey National Poetry Month celebration reading on Zoom. Each of us were to read a piece or two amongst a host of other talented writers. When we “rehearsed” our poems we ended up doing bits and goofing off for most of it. That’s when we became friends.

Joy Deficit

In April, I also ended up reading some poems as part of a show called Joy Deficit hosted my comedy heavyweight and Atlanta legend Gina Rickicki. The show is centered around filling up the reserves of joy that are drained by modern living. Each individual is layered with a theme. I applied for the show themed on “comfort” and read poems about trans joy and romance. It was an exquisite pleasure to perform around musicians, puppeteers, other writers, and acts so esoteric they defied genre. It’s a stage and a group I loved so much that I’ve been back as many times as I can schedule and as often as they’ll have me.

The Z Word with Lindsay King-Miller

In June, just in time for Pride, my friend Lindsay made her fiction-writing debut with her horror action apocalypse romp of a novel, The Z-Word. When I told my favorite bookstore about the book, they leapt at the chance to host a reading and conversation with Lindsay. When it was time to fill the other seat in the conversation, I offered up some names, but ultimately Lindsay asked if I would do it. Despite writing and messaging for literal years, this would be the first time in ages we ever spoke to each other with our voices. We talked horror, problematic queerness, and I embarrassed myself praising her absolutely kickass book. You should buy it.

What Was Eaten Was Given Release Party

This year’s crowning achievement for me was the release of my debut poetry collection What Was Eaten Was Given with my publisher, Kith books. The book was such a massive labor of organization, writing, compilation, and creative stamina that to finally release it into the world was like the heaviest and most satisfying sigh. Then, shortly after, I was privileged enough to be a featured reader at my favorite bookstore, Charis Books to launch it. All my friends, my girlfriend, and family came to support me. I felt like the prettiest girl in the world, like a princess. I still do.

Monster Show for Monsters

One of the best times you can have in Atlanta is at the Monster Show for Monsters. With monthly variety shows featuring burlesque, drag, music, and comedy all celebrating monsters and queerness and fearless self-expression, it’s a riot of a time. Hosted by undead roller skate waiter Boris Karhop and inter-dimensional playing card demon Jack of Diamonds, the show consistently delivers experimental, engaging and often hilarious work. I was given the chance to read some of my cannibal love poetry in the persona of The Bog Librarian of Chanterelle, Georgia:

After the library sank into the bog, the head librarian of Chanterelle, GA survived by getting stranger. She learned to breathe mud, to drink blood, and to read and write the kind of poems that should never breach the surface. Lucky for you, she has crawled free of the muck to read these forbidden texts to shock you, to horrify you, and to turn you on.

It was an absolute blast to be able to read alongside these weirdos. I’d love to do it again sometime.

Chit Chat Club

This year has also been devoted to writing poems about my breasts for a possible collection. Inspired by artists like Henri Riviere and Hokusai, I decided to dedicate my time to capturing ekphrastic moments of my changing body in poems. When I found out The Bakery, an arts organization here in Atlanta, was hosting salons where people could talk about their craft, I pitched them a talk about my tit poem project. Sharing the stage with talks on Marionettes, Marvel theme park rides, and jiu jitsu, it felt a little silly to talk about my breasts, but luckily everyone seemed on board.

Horrors We Desire

Lastly, I applied to perform alongside burlesque acts and performers once again, this time for a one-off night of performances all about the Monsters We Love. Naturally I wrote about falling in love with The Fly from the The Fly. As the only non-burlesque performer, I felt incredibly awkward but incredibly lucky to wedge my little love letter in between stripteases from Lestat from Interview With a Vampire and Oogie Boogie from Nightmare Before Christmas.

To conclude, I offer you this:

There’s a story about the Ancient Greek lawmaker, Draco, about how he solicited support from his people when his strict and punitive laws were called into question. The people offered their support by flinging their hats and coats and cloaks at the lawmaker’s feet. The love they had for Draco was so overwhelming, however, that they smothered the lawmaker, drowning him in comfort and love and coats and hats until he suffocated. That’s the myth of how the man died.

This year, choked with shows and support and poems and people and love, has felt like that. I’m exhausted and burnt out and frail as fine china, but, my God, I am grateful.

My God, I am warm.

Yours with an open mouth,

-B

12/12/2024

Burn out and best intentions

Burn out and best intentions

Next to my bed, on my barstool-as-nightstand, is a new alarm clock. It is equipped with an attachment that slips into my pillowcase. When my alarm goes off it is loud enough to wake up my neighbors’ neighbors, and the attachment shakes my bed like an 80s horror movie special effect. This is so I can wake up. I haven’t been sleeping well.

We are well and truly burnt out now that the year is coming to a close and the dark is tight around the neck like a Dracula cape. My initial strategy against Seasonal Affective Disorder (working like a dog both professionally and creatively while hurling myself at every available social regardless of scale, duration, or proximity) failed me to the point we’re at now.

I am steeped in exhaustion. I sleep often, I rarely leave bed (thank you again, work-from-home job), and my workout regimen which gives me joy (and sweet sweet dopamine) has left my daily routine and become a hazy memory. More often than I run I find myself remembering fondly the last time I ran, like a highschool trackstar caressing both her first place medal and her bum knee in tandem.

Last week I performed twice. In between work, sleep, and languishing I got my ass out of bed, into a lovely outfit, and down to a performance venue to read some work. After Wednesday, another literary brawl at WriteClub Atlanta, I passed out for, earnestly, twelve hours. Upon waking, the fact that I had a second performance in a burlesque variety show a mere three days later hit me with apocalyptic force. Worse yet, I had not yet written a word of what I was slated to perform that evening. It was months ago when I applied for either show. The wolf of my hubris had all that time to whet its terrible teeth into something that could bite through my thigh.

I love performing. I get genuine energy from it. I’m convinced that it’s one of the key dozen-or-so reasons I never found any success writing longform prose or developing videogames. Too much of novel-writing or game development occur within the hermitage.

But I finally pulled it all together the morning of the show, and while I loved performing and spending time with the burlesque acts (always a wonderful thing to share space with artists of a completely different discipline than me) I knew my battery was blinking behind my eyes. I was in the red.

I have been since the end of October.

I look forward to the end of these dark days and until then, I will be John the Baptist. My dark honey and locusts will be the occasional phone calls with a girlfriend, minutes in front of my Happy Lamp (tm) or couple hours of sleep. I will await the return of my prophet. I have been avoiding everything from bible study to church to walks around the neighborhood. I am in my enclosure. I am atop my pillar. I am praying until I see the light. I know it is coming. The sun will be glorious as any savior. It will save me. It always does.

My girlfriend just met her own dawn as she finished up her latest semester at school. Her last exam was today and she celebrated with a tiny bottle of champagne, a plate of tacos, and the merciful permission to be, in her words, “a dumb bitch again.” After the way this semester has pushed her intellect and her fortitude, she deserves it.

We all do.

But until then, my ultra-loud super alarm will make sure I wake up on time.

Yours with an open mouth,

-B

PS. I’ve attached a copy of my performance piece from the Saturday Show here. Enjoy?

12/12/2024 (Suppl.)

Get in the Telepod: Love Letter to Brundlefly

Get in the Telepod: Love Letter to Brundlefly

My love,

When you gripped the barrel of that shotgun, pressed it to your antennae'd head, and wordlessly begged Gina Davis to shoot you, I cried like my dog died. Like I was a child again, screaming "No!" as Scar let Mufasa hit the ground. I was ruined...even though I had watched you die a hundred times by then.

I first met you when I was sixteen. And I didn’t understand you. You terrified me. You made me uncomfortable. Looking back now. I see you as you are.

My Brundlefly, before the change, in all your twitching nervous, your long hair and uncomfortable suits, you looked like every one of my wedding photos:

Happy from the neck up, looking like you wanted to shed your skin like so much meat sloughing off of chitin. Watching you again, at 30, I finally recognized that look.

I saw the Fly again right after I started hormones. Right after I looked at my body and decided to get mad science involved. When you told Gina Davis that your machine takes you apart and puts you back together somewhere else, I knew what you meant.

Within days of my first dose, I could feel the hard and unforgiving angles of my boy body melting, dissolving like film stock, like liquid latex, like the rounded edges of the estradiol under my tongue.

I wanted to melt with you. I wanted to be purified and glopped together by an accident of science in the body I deserved just like you did.

Because even as Jeff Goldblum won arm wrestling matches and did gymnastics and fucked Gina Davis to exhaustion I didn't want him. I wanted you.